-

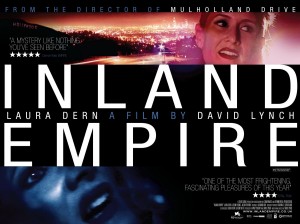

‘INLAND EMPIRE’ (2006): A FILM BY DAVID LYNCH

November 15, 2012

Essays on Film

Essays on Film -

‘To me, a detective is the most magical type of character, because mysteries are to me the greatest thing. Puzzles and things like this are thrilling, clues, things like finding money. Everything is a mystery and we’re all detectives. Even scientists are detectives and they’re all looking for clues to solve the big mystery. There are so many detectives going around, and so many mysteries’.

‘To me, a detective is the most magical type of character, because mysteries are to me the greatest thing. Puzzles and things like this are thrilling, clues, things like finding money. Everything is a mystery and we’re all detectives. Even scientists are detectives and they’re all looking for clues to solve the big mystery. There are so many detectives going around, and so many mysteries’.This from David Lynch, a director whose films likewise force the viewer to assume the role of a cinematic sleuth. From his brilliant, enigmatic Eraserhead (1977) to the corrosive and confounding Lost Highway (1997) and the dark, morbid masterpiece Mulholland Drive (2001), one is confronted with mysteries that get increasingly elusive with each frame; clues that confound logic and sense, leads that result not in a clear dénouement but in riddles, puzzles, sleights of perception, tricks of the mind.

In Lynch’s stark, visually ensnaring but bewildering universe, nothing is quite what it seems and nothing remains stable; the same actor mutates into different roles, objects are charged with a sinister, chameleonic power, time assume a soft, fluid plasticity, seemingly mundane sites and spaces cunningly transport you to strange and foreign realms. This uncanny sensibility reaches terrifying and ferocious extremes in Inland Empire (2006), Lynch’s vast, ambitious magnum opus.

Nikki Grace (Laura Dern) is an actress who secures the top female role in a major Hollywood film alongside leading man and notorious womaniser Devon Berk (Justin Theroux). Titled ‘On High in Blue Tomorrows’, the film is attached to the charming but reticent director Kingsley Stewart (Jeremy Irons). Production begins with ceremony and pomp; champagne is poured and sipped, the actors’ egos are pampered, the director indulges in self-adulation. When rehearsals commence, however, a darker mood sets in.

Reciting their lines before Kingsley and his shady assistant Freddy, Nikki and Devon are interrupted by a palpable but invisible presence on the set. Demanding an explanation from the director, Kingsley begrudgingly informs his two stars on the film’s morbid and gruesome history (one purposefully concealed by the producers): On High in Blue Tomorrows is a remake of an earlier film that was never finished. Based on a polish gypsy folk tale, the original film was said to be cursed, a rumour that was confirmed by the subsequent murder of its two leads.

From this point forth, we are propelled, like Alice in Wonderland, down the Lynchian rabbit-hole, where it becomes increasingly impossible to distinguish the world of Nikki and Devon from that of their counterparts Susan Blue and Billy Side (from ‘On High in Blue Tomorrows’). To complicate matters, Uncle Lynch transports us, via door ways, hall ways and stair cases, into the parallel worlds of talk shows with scathing hosts, sitcoms with Rabbit people and canned laughter, European neighborhoods with gangsters and gypsies, Hollywood Boulevard with its femme fatales, fading stars and fallen prostitutes.

With Inland Empire Lynch manages to visualize a hyper real America envisioned by the late, self-dubbed ‘intellectual terrorist’ and (anti)sociologist Jean Baudrillard: ‘It is not the least of America’s charms that even outside the movie theatres the whole country is cinematic. The desert you pass through is like the set of a Western, the city a screen of signs and formulas…The American city seems to have stepped right out of the movies. To grasp its secret, you should not, then, begin with the city and move inwards to the screen; you should begin with the screen and move outwards to the city. It is there that cinema does not assume an exceptional form, but simply invests the streets and the entire town with a mythical atmosphere. That is where it is truly gripping’.

Indeed, one of the film’s most ensnaring scenes is its indeterminate climax where a prostate, bloodied and seemingly dying Nikki Grace (or is it her alter-ego Susan Blue?) emerges from the star-lined Walk of Fame, stumbles past the camera and crew, walks beyond the set and into the confines of a movie theatre, her eyes fixated on the screen that projects her every move in real time. ‘The thing is,’ Nikki/Susan explains, ‘I don’t know what was before or after. I don’t know what happened first, and it’s kinda laid a mindfuck on me’.

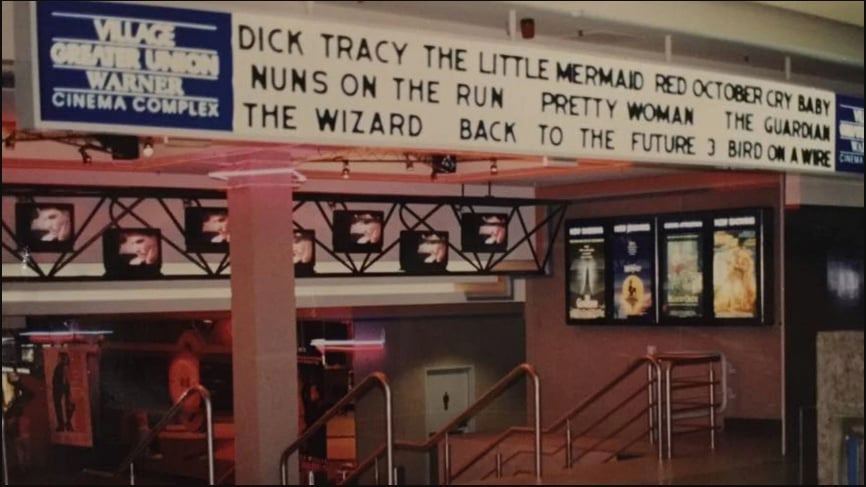

Inland Empire is a mindfuck: convulsive, excessive, surreal. This is on account of its dream-like sequencing of image and sound, its coarse, grainy aesthetic (it was shot entirely on standard definition digital video) and its ironic and amusing casting. Lynch, like Quentin Tarantino, is infamous for including obscure, emerging or fading celebrities in his films: Lost Highway delivered cameos from Henry Rollins and Richard Pryor, while Mulholland Drive featured Billy Ray Cyrus, Marcus Graham (Wheels from E Street), Melissa George and Lisa Lackey (of Home and Away fame). In ‘Inland Empire’ we encounter another Los Angeles-based, expatriate actor. Cameron Daddo, the host of ’80s dating game show Perfect Match, surfaces for his fifteen minutes of fame as Devon Berk’s disapproving manager.

At three hours, Inland Empire is a tortuous, frightening and mystifying epic: a monstrous, haunting homage to Hollywood where freakish, alternate realities and parallel worlds (cinematic, televisual, musical) converge and dissolve leaving the viewer, much like the troubled, leading actress in On High In Blue Tomorrows, at once disturbed, seduced and startled: ‘I guess after my son died, I went into a bad time when I was watching everything around me while I was standing in the middle, watching it like in a dark theatre before they bring the lights up’.

– Dr. Varga Hosseini