-

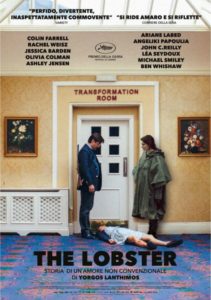

‘THE LOBSTER’ (2015): A FILM BY YORGOS LANTHIMOS

August 26, 2015

Film Reviews, Updates

Film Reviews, Updates -

What does it mean to be human? How are we different from other species? If our humanity were in question, what type of animal would we choose to become? Would our preference impact on the way that we perceive and treat others? If one of the dimensions of being human is the pursuit of personal freedom, how is this negotiated in an increasingly bureaucratic world? And at what price?

I find myself pondering these slippery and elusive questions after viewing The Lobster (2015), co-writer/director Yorgos Lanthimos’ follow up feature to Alps (2011) and his first English language film. Intelligent, perceptive and darkly humorous, it paints an expansive, timely and morbidly entertaining portrait of the struggle for survival in a world where loneliness and individuality have become anathema to a culture of heightened conformity and ubiquitous surveillance.

In the not-too-distant, dystopian future, single citizens are transferred to an ominous hotel where they are granted forty-five days to find a mate or risk being transformed into an animal of their preference. During the course of their stay, they submit to stringent monitoring, partake in regimented activities, and are trained in the practice of hunting a community of “loners” who reside beyond the hotel’s enclosure.

It is an estate slightly reminiscent of the villa in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), where self-pleasure is prohibited and mercilessly punished (there is an unnerving scene of a hand being thrust and lodged into a live toaster), intimacy is controlled and regulated, friendships and alliances are manipulative and opportunistic, and the operation is run by a commanding, all-singing, all-dancing hotel manager and her portly husband.

We are transported to what is, in effect, a processing plant for singles where sumptuous scenes of feasting, leisure and merriment are interwoven with supervised hunting sprees and outbursts of violence captured in classically-scored, slow-motion cinematography. While not your typical house of horrors, the occasional bloodied corpse or agonisingly injured body does surface, splayed in a hotel bathroom or sprawled across its patio.

It is into this kooky setting and its predatory social hierarchy that newly single divorcé and mild-mannered architect David (Colin Farrell) arrives with his beloved and cautiously protective pet dog, Bob, by his side. Upon entry, a receptionist methodically records his personal details (even delving into his sexual orientation), while the manager personally greets him and enquires into his animal of choice. His preference? The film’s crustacean namesake. His reasoning? Lobsters can live for a hundred years, are blue-blooded creatures (‘like aristocrats’), and share his fondness for the sea.

While his marksmanship and hunting prowess require improvement, David succeeds in forming tense but amicable friendships with some of his fellow guests. His cunning attempt to locate a partner through ruse and deception, however, goes horribly and gruesomely awry, prompting his escape from the hotel and his foray into the verdant world of the “loners”. Picture, if you will, a Lord of the Flies for singles who are older, wiser, slightly less feral but zealously fanatical.

This forest abode is itself a nutty world with an even nuttier set of rules and protocol. Strictly monitored by the icy gaze of a seldom-smiling Loner Leader (Léa Seydoux), it is a microcosm where electronic music and solitary dancing are acceptable forms of entertainment, freshly procured rabbit is the cuisine of choice, while flirting and tonsil-hockey are severely reprimanded. But when an impassioned romance blossoms between David and a nameless, myopic loner (Rachel Weisz), even the Spartan order of this austere, arboreal environment is disrupted, forcing the inseparable couple to flee and seek sanctuary in another domain: the towering, Orwellian, postmodern metropolis.

As with his acclaimed but controversial second feature Dogtooth (2009), The Lobster extends and hones Lanthimos’ concern with enclosure, territoriality, and the traffic and interchange between interiors and exteriors, insiders and outsiders, humanity and animality, civilisation and savagery.

There is a surrealist edge to his aesthetic sensibility where seemingly familiar and even mundane sites become comically uncanny, strange and unhinged, radiating an opulent and foreboding beauty. From the carceral confines of the suburban family home, to the efficient industrial complex of the hotel, and the zombie-like subculture of the forest, the absurd social dynamics at work in these settings invite us to reflect on the institution of borders and limits, their vulnerability and fragility, and their openness to defiance and transgression.

Film critic Robbie Collin delightfully construes The Lobster as ‘a loopy deconstruction of the contradictory social pressures to pair off and stay single’. For it is a film in which the human animal is a different creature in different contexts, mutating across time and space, its desire and pursuit of freedom, intimacy and love always entailing an exorbitant cost, from the painful loss of a loyal companion to the potential enucleation of our privileged sensory organ: the eyes that simultaneously reveal and blind us.